A view from the Shoreline Apartments towards downtown Buffalo, early 1970s. Photographer unknown.

© The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Courtesy of the Paul Marvin Rudolph archive, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

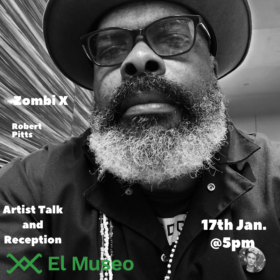

El Museo presented Shoreline: Remembering a Waterfront Vision, a special project that looks into the history of Buffalo’s Shoreline Apartments, a housing complex designed by architect Paul Rudolph. The project will open with an exhibition of drawings, photographs, documents, and artworks, spanning from the original vision of the Buffalo Waterfront Development in the 1960s to the eventual destruction of Shoreline in recent years. The exhibition will be on view at El Museo from October 4 to November 16, 2019.

A public symposium on October 25–26 convened architects, urban planners, preservationists, and researchers to discuss Paul Rudolph’s design legacy in Buffalo and New York State, the social legacy of urban renewal and modernism, and preservation efforts surrounding these sites and structures. This event will take place at the Earl W. Brydges (Central) Library in Niagara Falls and at the Frank E. Merriweather (Jefferson) Library in Buffalo.

The playlist for videos of the symposium is available on Youtube at this link.

Forthcoming in 2022: A publication will bring together images, essays, and other findings from the project to tell the varied histories of the Shoreline Apartments.

Background

Located steps from City Hall in Buffalo’s Lower West Side, the Shoreline Apartments is a housing complex designed by architect Paul Rudolph and completed in 1974. Featuring shed roofs, ribbed concrete exteriors, projecting balconies, and enclosed garden courts, the project combined Rudolph’s spatial radicalism with experiments in human-scaled high-density housing. It was originally part of the Buffalo Waterfront Development, an ambitious, mixed-income urban renewal project commissioned by the New York State Urban Development Corporation in 1969. Rudolph’s scheme featured an arrangement of monumental, terraced high-rises flanking a marina, a sprawling school and community center, and a series of slinking low- and mid-rise apartment buildings meant to evoke Italian mountain villages, with green spaces woven through the site.

“With few exceptions, Paul Rudolph’s buildings can be recognized by their complexity, their sculptural details, their effects of scale and their texture,” wrote Arthur Drexler, Director of the Museum of Modern Art’s Architecture and Design Department for his 1970 exhibition, Work in Progress, which included Rudolph’s plans for the Buffalo Waterfront Development and Niagara Falls Library, among others. The projects, he suggested, reflected “a commitment to the idea that architecture, besides being technology, sociology and moral philosophy, must finally produce works of art if it is to be worth bothering about at all.”

In the end, only two phases of affordable housing (Shoreline and Pine Harbor Apartments) were built. Today they are among the most hated buildings in Buffalo. Like many public housing contemporaries, their inventive, complex forms and admirable social aspirations have been overshadowed by disrepair, crime, and vacancy. Norstar Development, the site’s owner, in 2013 proposed a phased demolition and replacement of Shoreline with new Victorian-style townhouses. Following failed attempts at landmarking the structures for preservation, the first round of demolitions began in summer 2015. In 2017, Norstar accelerated the demolition schedule, asking remaining residents to leave, and in January 2018, the last holdout was vacated from his unit.

The demise of the Shoreline Apartments represents not just the loss of an exemplary piece of Buffalo’s architectural legacy, but also the death of a certain perspective on architecture and the city. It tells a story of the hubris of midcentury urban planning, the short-lived heroism of brutalist architecture, and the unrealized social visions of the past. Perhaps for these reasons, there has been apathy towards, even disdain for, structures of that era such as the Shoreline, and public housing in general. In Buffalo, major modern landmarks such as Willert Park Courts, Commodore Perry Projects, Glenny Drive Apartments, and Marine Drive Apartments are variously deteriorating, vacant, or demolished.

At a time of renewed interest in modernist and brutalist buildings, this project asks critical questions about equity in architecture and historic preservation. Whose buildings are important? Whose stories get told? What types of structures are considered worthy of maintenance and protection, and what others are left to deteriorate and die? Is there room in our cities for inconvenient reminders of a past we would rather forget? Through the lens of the Shoreline Apartments, this project aims to inspire new conversations that might lead to a better understanding and appreciation of these misunderstood artifacts.

Project Credits

Shoreline: Remembering a Waterfront Vision is curated by Bryan Lee and Barbara Campagna, and presented in partnership with the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

This project is funded by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature, and the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts.

![]()

About

Founded in 1956, the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts fosters the development and exchange of diverse and challenging ideas about architecture and its role in the arts, culture, and society.

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation has a mission to preserve and protect Paul Rudolph’s work, to educate the public about the legacy of his philosophy, and to provide a gathering space for discussion about modern architecture. Established in 2015, the PRHF is located in the Rudolph-designed Modulightor Building (246 East 58th Street) in New York City.

Barbara Campagna has worked for the past 30 years as an architect, planner, and historian, and was inducted into the AIA College of Fellows in 2009. She has lectured extensively, organized many conferences, serves on a variety of nonprofit boards, is the author of two books, and has held faculty appointments at the University at Buffalo and FIT in New York. Recently, she was a prominent voice in the campaign to save the Shoreline Apartments from demolition, and taught a graduate seminar, “Preserving Modern Heritage,” which documented Buffalo’s modern architecture for the Docomomo US Registry.